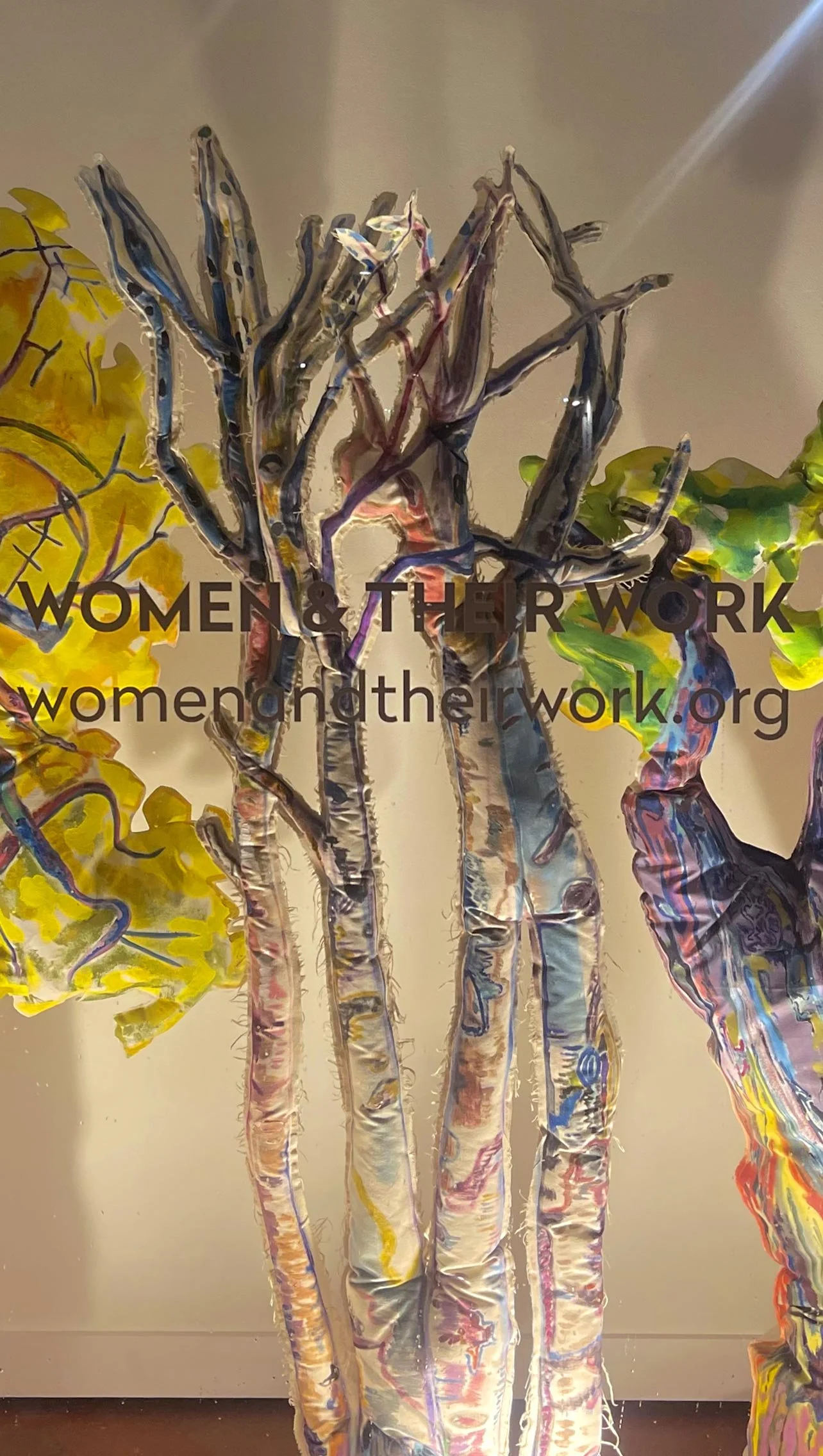

Lichen Lace Yellow Maple, Birch Entanglement, Grandmother Maple, 2022

Walking through Menil Oak

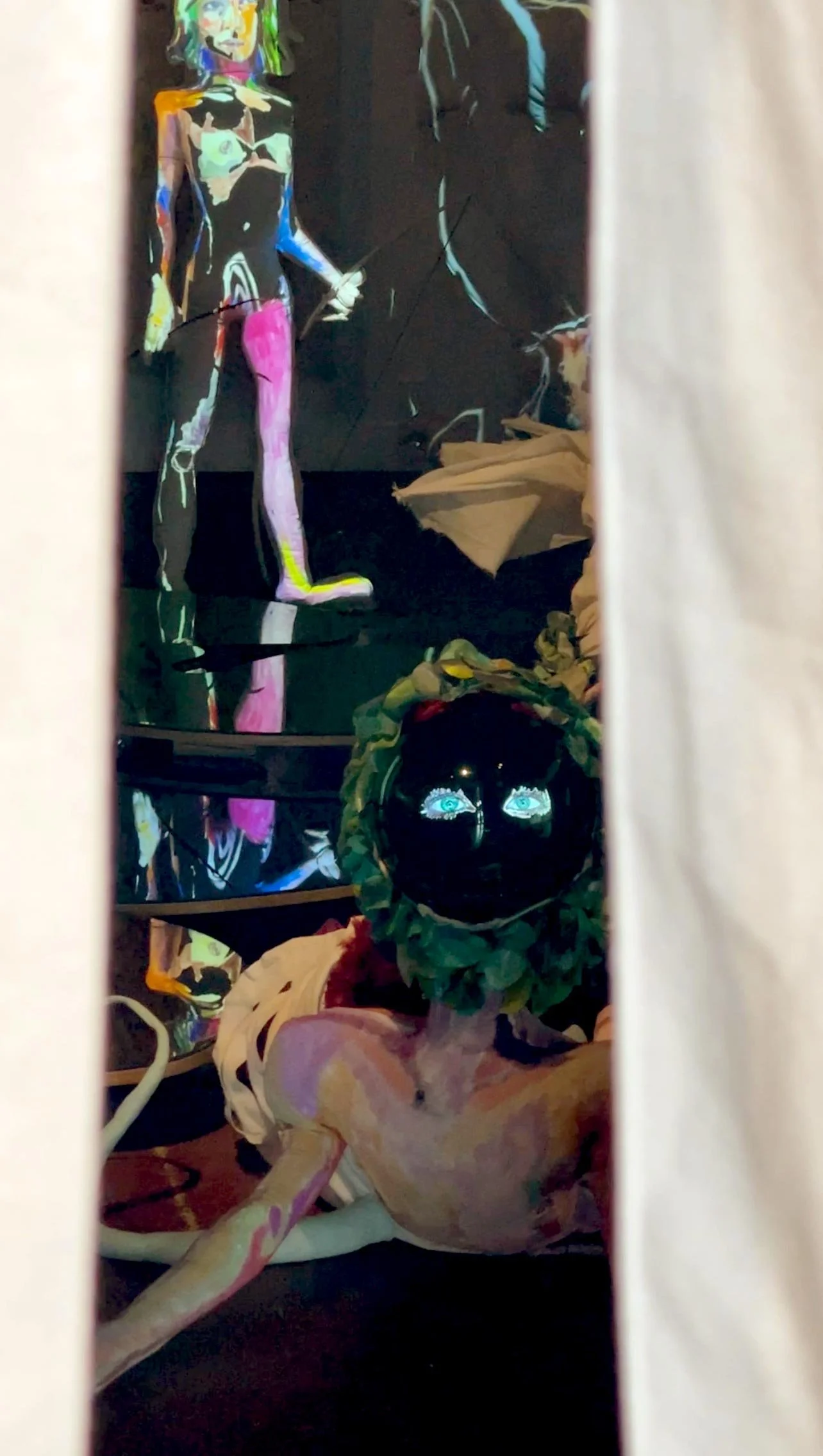

Stag, acrylic on canvas, polyfill, cedar branches, steel, video monitors, pink LED light bulbs, paint rags, bone buttons, whittled sticks, string from decades of painting badminton court lines for the artist’s children, gold leaf, silk velvet, yarn, wire, crochet, projections of artist’s dogs’ fur, 63 x 30 x 60 inches, 2022-2024

Photos by Women and Their Work and Christie Stockstill

Treespell Perfume, Treespell was created in collaboration with Texas perfumer Chavalia Dunlap as an olfactory component to this exhibition. The scent was intentionally pushed to live on the edge of wearable, with a deep forest musk of cedar (the mystical tree of Artemis), beasts vetiver, and rot. Middle notes of moss, pond water and earth soften and the hay-like brightness of fern shimmers as the top note. 2022-2024

A painting pretending to be a forest, pretending to be a tree my kids hid inside, pretending to be a sentinel at Barton Springs. A tree pretending not to notice our not noticing, me trying to notice as hard as I can.

I love the myth of Artemis, the forest huntress, goddess of wild animals and plants and birth. When a hunter stumbles upon her and her nymphs bathing in the forest, Artemis turns him into a stag, who, in most tellings, is devoured by his hounds, or in some tellings, is shot through by the goddess’ arrows. Artemis is the gaze destroyer, “militating against viewing”. I am exhausted with self-expression, my own especially. I am exhausted by my eyeballs, by images, by seeing so much all the time and wanting to see so much all the time. Yet I am a visual artist. I bumbled into the process for this exhibit, which (mostly) feels like an antidote.

I started for two reasons.

One: how can a portrait be an action? Instead of choosing one moment to “present” for “viewing,” how can the painter and painted co-become? What is gaze in the light of our entanglement? This started with painting a baby in his mother’s arms. He was pure to the process, fidgeting, fussing, and laughing. By painting this baby’s face over and over on the same canvas, documenting each iteration with my camera before obliterating it with new brush strokes, I destroyed the work as product and created my own medicine. And something else started to happen. There is a point in the painting when the baby is both irritable and pacific. Or, for the stag's eye screens, I painted the eyes of Putin and then on top of this, Rilke, Walt Whitman, MLK and so on (400 frames in all). There is a point in the painting where the eyes are both Putin and Rilke, then more Rilke, then fully Rilke; where the eyes are both Hitler and Russell Brand, then more Brand, then fully Brand. These in-between spaces become entanglement, simultaneously obliterative and intermingling.

Two: I like the idea of paintings being ghosts of themselves, an echo of our collective ghost presence in the digital realm. Our fractured attention is glued to the ghost glow of screens, and what we do and look like feeds this ghost glow. I continue to be interested in taking computer generated imagery and making it painstakingly handmade, or in this case, taking something handmade and making it digital –in a cheeky way, not a clean way. Like a slick format for a very not-slick process. What is primordial – a painted image – pretending to be something new – an AI image, a digital utopia.

A forest holds our shadow while pointing to the mother of all myths, the tree of life, which holds us all in our shadow and our light.

A painting pretending to be a forest, pretending to be a tree my kids hid inside, pretending to be a sentinel at Barton Springs. A tree pretending not to notice our not noticing, me trying to notice as hard as I can.

A painting pretending to be the guardian of this forest, pretending to be a doll made for my past self, a tender Velveteen horcrux, and, most importantly, a real girl whom I have known and loved for 20 years.

A mirror pretending to be a puddle, pretending to be a pond in Vermont, my favorite screen, a portal content to stay put, holding every kind of green.

A painting pretending to be a sculpture, pretending to be me and my daughter, pretending to be fish, pretending to become, to unbecome, always loving the girl who guards the forest.

Me pretending. Pretending every day. That I am ok. That we are ok. That trees are ok. That making things makes things ok. That painting flesh, mine and those I love, human and otherwise, transubstantiates longing into reunion.

How can a portrait be an action? Instead of choosing one moment to “present” for “viewing,” how can the painter and painted co-become?

I like holding my questions in the container of myth. Emanuele Coccia in his book “The Life of Plants” says “the fact of being contained in something coexists with the fact of containing this same thing. The container is also the content of what it contains.” Both mythology and art contain my questions, contain me. Artemis and art making embody and dissolve gaze, embody and dissolve object. Also, I like forests. Whether it is Little Red Riding Hood’s, MacBeth’s Birnam wood or Lilith’s sanctuary/exile, a forest holds our shadow while pointing to the mother of all myths, the tree of life, which holds us all in our shadow and our light.

I came to this forest through fairy tales and recently through Emanuele Coccia, who centers plants in a world of total immersion where there is no separateness or other. As Alan Watts said “the only possible single event is all events whatsoever. The only possible single thing is everything.” or as Coccia would say “the world is one species. We are in something with the same intensity and same force as that something is in us.” The intimacy we feel with this mixture – this world that we contain and which contains us, helps us both dissolve our identity and caress it, unpeel and release what we think the world is so we can help birth a new one.

“....a sanctuary was erected because the spot was holy.”

‘These Wilds’

To enter Treespell, with its darkness infused with ever-changing growing vegetal light, is to be inside a kaleidoscopic sacred grove, a mashup of forest, church and mythic stage. A space in which Chapin tries to touch the world’s white-hot engine. Outdoor wilderness is now inside, held precariously in the domesticated gallery space. The use of outdoor space for cathartic rituals, religious or otherwise, has been marked historically by a rejection of the traditional church space, with its entrenched doctrines and a move toward the unstructured, the unknown and a closeness to divinity, not patriarchal or abstract, but encoded in leaves, branches, roots, flesh and water. “We make a sacred grove holy,” writes the Greek scholar Martin Nilson, “by putting a sanctuary there, but in antiquity the holiness belonged to the place itself and a sanctuary was erected because the spot was holy.” This paradox lights up Treespell with Chapin’s morphing effervescent trees and the mythic figures of the hunter goddess Artemis and her nemesis Actaeon. In Chapin’s retelling, Artemis is a creature moving from girl to woman, not peacefully but with all the blood and gut intensity of birth. Working from snapshots of her daughter’s friend, aged 6 to 24, Chapin photographed each portrait before painting over to create the next one. In the video projection, just as the trees around her mutate and glow, Chapin’s goddess melts and radiates. Artemis, who at the height of her popularity was worshiped in dozens of Greek temples, was a multi-faceted deity. She went by many names: Lady of the Beasts, Deer Shooter, Revered Virgin. She is associated with both water and the moon, particularly the phase of the moon closest to the new moon, when the silver sliver looks like a bow. Artemis was fiercely protective of female bodies; she punished men who killed pregnant deer and was known to change her nymphs into reeds, rocks, and springs in order to protect them from rape. Her grateful nymphs created a gushing fountain to please her and stocked it with huge sacred fish and a giant tame eel.

“...the tree is part of a central creative flow, an accelerated version of both Chapin’s practice, and of nature’s.”

For Chapin, Artemis is a “gaze destroyer.” When Actaeon is discovered hiding in the bushes, spying on the goddess and her nymphs bathing in a stream, she turns him into a stag and then kills him with her bow. The Stag, a soft fabric sculpture, is projected with fur from Chapin’s own dogs. It’s eyes, another projection, move through colorful paintings of eyes of real men, the artist’s father, husband, and son as well as both icons like Mr. Rogers and Nick Cave and controversial figures like Donald Trump and Elon Musk. It’s in these labor- intensive particulars that Chapin’s art awes; the wounds inflicted by Artemis’ arrows are tiny lips sewn with red thread and the animal’s testicles, crocheted with pink yarn and lit, like embers, from within, are a sign that while deactivated for now, male sexual insistence, like the villain at the end of a horror movie, is still very much alive.

The myth unfolds within the sacred grove; mirrored pools, fronted by two nymphs, mermaid/alien hybrids, are encircled with trees that move and expand like amoebas stained with all the colors of the galaxy. Chapin photographed the branches at different stages as they were painted, so the tree is part of a central creative flow, an accelerated version of both Chapin’s practice and nature’s. The trees’ stop-action movement in the darkened room reminded me of that most enigmatic part of plant life, roots. Roots have always haunted me. Recently I dumped out a small pot that held a dead narcissus, though the stem and flower were brown, the roots remained almost creepily alive, forming a sort of pot-shaped sculpture of wormy white plant flesh and dirt.

“Is it the unseen face (of God)” writes Emanuele Coccia in his book The Life of Plants,” that plants allow us to contemplate.” The root takes us closer than a perfect leaf or a flower to an elemental energy. “The root is like a second body,” Coccia continues, ”secret, erotic, hidden: an anti-body, an anatomical anti-matter that reverses in a mirror, point by point, everything the other body does...” Roots are one manifestation of The Other. They move in the Upside Down, a shadow world, their blind and urgent seeking depends on rot, decay and death.

Monsters, Timothy Beal writes in his book Religion and its Monsters, “represent the outside that has gotten inside, the beyond the pale that much to our horror has gotten into that pale.” Treespell emits an uncanny energy. The thrust of nature, like God, does not fit into rigid ideas of good and bad, the confines of our limited human subjectivity. Chapin’s particular genius is, while respecting multiplicity, pulling the wild into the woman-made. “Monstrosity,” writes Bayo Akomolafe in his book These Wilds Beyond our Fences, “is our entanglement with everything, a story of borders and bodies that are open and fluid, a madding insistence that we are always affected by the terroir of place.”

“Could wonder and beauty be components of the monstrous?”

Is monstrosity always negative? It’s worth noting that when angels appear to humans in the bible, the first thing they say is Be Not Afraid. Could wonder and beauty be components of the monstrous? Redbud makes me think so; projected onto a soft tree sculpture, the artist’s hands tinted red, flutter and wave, like flowers or flames, and are reminiscent of the disembodied and floating hands in 19th century spirit photographs. They beckon us toward a fenestral opening, the one I tried to find relentlessly as a child, by pulling myself inside our giant lilac bush and running down the hill as fast as I could in my mother’s old prom dresses. Chapin is interested in “ocular portals” like Redbud’s wound-like hands and the mirrored pools that glow at Treespell’s center. A tear, an opening that leads not to another dimension, but the wildness inside ourselves. “All life forms,” writes Merlin Sheldrake in his book Entangled Life, “are in fact processes.” Efforts have been made to name the force that drives the green stem or what Chapin calls “sacredness composting humanity.” The 13th century mystic Hildegard of Bingen called it viriditas, ever-greening, the vegetal being and the mystery of elemental expansion—not limited to plants and a key component of human spiritual growth. “One grows forth, “writes the philosopher Michael Marder in his book Green Mass, “as the other, the viriditas, freshness, or greening—of the othering of life.” Or as Chapin explains visually in this ambitious show that attempts the impossible: to harness the life force itself, we can’t be young but we can always be new

Darcey Steinke is an author based Brooklyn, NY